Are CoCo bonds still investable after the CS deal?

Are CoCo bonds still investable after the CS deal?

CoCo bonds (contingent convertible bond) are conditional mandatory convertible bonds. This is a loan to a bank that is counted towards the bank's equity capital in the event of a crisis. A bond investment with fundamentally lower risk thus becomes an equity-like investment with high risk. The definition of what a crisis is will be determined on the one hand by certain threshold values in relation to the core capital or is decided by the supervisory authority, as we have seen at the latest since the events surrounding Credit Suisse. CoCo Bonds were introduced in Europe after the global financial crisis in 2008 to serve as shock absorbers when banks began to wobble. They are structured as subordinated debt, and are designed to meet regulatory capital requirements under Basel 3[1]. CoCo Bonds are a hybrid form of financing and combine the usual characteristics of a bond, in particular the fixed interest rate, with the loss-absorbing capacity of equity. Depending on their structure, these bonds are listed in different categories in banks' balance sheets: Additional Tier 1 (AT1) or Tier 2, the former being "closer" to equity. AT1 bonds are an integral part of a bank's capital structure. They are a way for banks to fund themselves at a lower cost than would be possible, for example, through a share capital increase.

As you can see: This kind of instrument is highly complex.

What happens when a bank loses money?

The bonds are designed to absorb losses in two ways: The first is through partial or full suspension of interest payments at the issuer's discretion, and the second is either through a write-off of the nominal amount or through a (full or partial) conversion of the nominal amount into equity. When a bank's core capital ratio (CET 1) falls below certain thresholds - usually around 7% or 5% - this triggers a mechanism (trigger) and the bonds then usually convert into shares. The aim of this is to reduce a bank's liabilities in the event of falling capital ratios, thereby strengthening equity again.

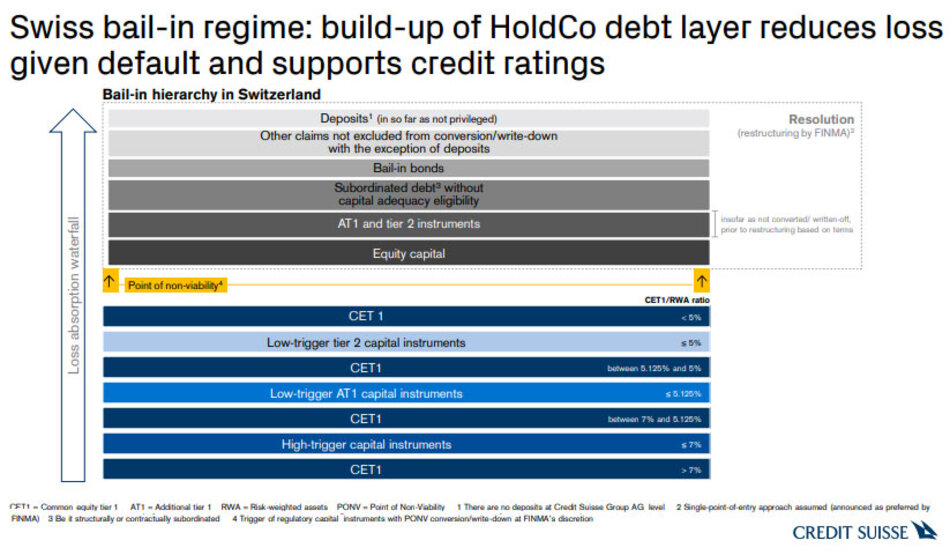

In the grey section above, the figure shows the step-by-step loss absorption process created by FINMA. It indicates who bears the losses first. This procedure is similar to the order in which creditors are satisfied in a bankruptcy collation plan.

The expectation according to the diagram would be that the shareholders would be the first to bear any losses and only then the aforementioned AT1 investors. This is one of the main reasons why financing through the issue of new shares would have to be the most expensive for a bank: those who bear the highest risk usually demand the highest risk premium.

What went differently with the takeover of CS by UBS?

According to Federal Councillor Keller-Sutter, the state-orchestrated takeover of CS by UBS was a deal between two private companies. According to current knowledge, shareholders will receive one UBS share for about 22.5 CS shares. Although CS shareholders will suffer a substantial loss, they will at least receive a small equivalent value for their shares.

The situation is different for investors in CS AT1 bonds: They suffer a total loss of about 16 billion Swiss francs, justified by (Swiss) emergency law! This, nota bene, in a situation where CS fulfilled the regulatory minimum ratios. The gradual absorption process was thus not adhered to!

In this regard, FINMA wrote on 23 March 2023: "The AT1 instruments issued by Credit Suisse contractually provide that they will be fully written off in the event of a trigger event (viability event), in particular when extraordinary government support is granted. As Credit Suisse was granted extraordinary liquidity support loans secured by a default guarantee from the Swiss Confederation on 19 March 2023, these contractual conditions were met for the AT1 instruments issued by the Bank."[2]

Are these instruments still investable?

The approach to this acquisition raises questions. If a bondholder earns a lower return (risk premium) than the shareholder in good times, but has to accept the greater loss in an emergency, who will still invest in such instruments?

Already in 2018, the German Bundesbank wrote in its monthly report: "Overall, it is questionable what advantages the use of CoCo bonds has over hard core capital". And further: "Rather, a focus on CET 1 capital (share capital) is likely to be the more target-oriented approach to securing and improving the stability of banks in the long term".[3]

Conclusion:

CoCo bonds are highly complex instruments that have had a raison d'être up to now. This should be questioned vehemently. It probably makes more sense for private investors to think back: If you want to be a shareholder in a company, buy its shares and benefit from the possibly higher risk premium. If you want to invest as a creditor, buy "classic" bonds of the respective company. These instruments are versatile and have proven their worth over the years! Warren Buffet's principle for shares is: "Never invest in a business you cannot understand.". Deriving from this, one could say: "Do not invest in instruments that you cannot understand!

[1] is the banking abbreviation for capital adequacy regulations that were published in a preliminary final version by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision based in Basel in December 2010. The predecessors of these regulations were Basel I and Basel II

[2]www.finma.ch/de/news/2023/03/20230323-mm-at1-kapitalinstrumente/

[3] Quelle: Deutsche Bank Monatsbericht März 2018, S. 65-66

We advise individuals and legal entities on all legal matters around wealth management and are a pioneer in impact investing, which is part of our entrepreneurial identity.

Our focus is on

✓ effort based charging

✓ impact investments

✓ avoiding conflicts of interests

✓ comprehensive overview of your total assets